|

Carl Larsson.org, welcome & enjoy!

|

|

|

Prev 1 2

|

|

Here are all the paintings of Michelangelo Buonarroti 02

| ID |

Painting |

Oil Pantings, Sorted from A to Z |

Painting Description |

| 52446 |

|

Separation of Light from Darkness |

1511 Fresco, 180 x 260 cm |

| 42656 |

|

Sixtijnse chapel with the ceiling painting |

MK169

1534-41 |

| 62878 |

|

St Anne with the Virgin and the Christ Child |

1505 Pen, 254 x 177 mm Ashmolean Museum, Oxford The challenge of this subject is the placement of one grown woman on the lap of another without creating an awkward appearance. Michelangelo dealt with a similar problem already in his Roman Piete a subject which required the placement of an adult male on the lap of a woman. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: St Anne with the Virgin and the Christ Child Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : religious |

| 63021 |

|

St Peter |

1501-04 Marble Duomo, Siena Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Painting Title: St Peter , 1501-1550 Painting Style: Italian , sculpture Type: religious |

| 63024 |

|

St Petronius |

1494 Marble, height: 64 cm with base San Domenico, Bologna In 1494 Michelangelo worked on the shrine of St Dominic, for which he carved this statue of St Petronius which echoes Donatello and Jacopo della Quercia. (The companion statue of St Proculus testifies to Michelangelo's studies of Masaccio and Donatello.) Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Painting Title: St Petronius , 1501-1550 Painting Style: Italian , sculpture Type: religious |

| 63025 |

|

St Proculus |

1494 Marble, height: 58,5 cm with base San Domenico, Bologna In 1494 Michelangelo worked on the shrine of St Dominic, for which he carved this statue of St Proculus which echoes Masaccio and Donatello. (The companion statue of St Petronius testifies to Michelangelo's studies of Donatello and Jacopo della Quercia.) Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Painting Title: St Proculus , 1501-1550 Painting Style: Italian , sculpture Type: religious |

| 62906 |

|

Study |

1525 Ink Casa Buonarroti, Florence The picture shows a study for the fortifications of Porta del Prato in Florence. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: Study Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : study |

| 62893 |

|

Study for a Deposition |

1555 Red chalk on paper Ashmolean Museum, Oxford Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: Study for a Deposition Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : study |

| 62879 |

|

Study for a Madonna and Child |

1533 Black chalk on paper British Museum, London Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: Study for a Madonna and Child Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : study |

| 62886 |

|

Study for a Nude |

1504 Pen and ink over black chalk, 408 x 284 mm Casa Buonarroti, Florence It is assumed but not proved that Michelangelo made this study for the Battle of Cascina. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: Study for a Nude Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : study |

| 62887 |

|

Study for the Battle of Cascina |

1505-06 Chalk and silver rod on paper, 235 x 356 mm Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence The attribution of this drawing to Michelangelo is debated. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: Study for the Battle of Cascina Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : study |

| 62880 |

|

Study for the Colonna Piet |

1538 Chalk Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, Boston In 1538, three years before the completion of the Last Judgment, Michelangelo had met Vittoria Colonna. She belonged to the circle of Juan Valdes, who was striving towards an internal reform of the Catholic Church. To put it very simply, one can say that the main conviction of this theological trend was the idea of the utmost need of faith, as opposed to good deeds or sacraments, because, in the last resort, it is only divine grace which is all-powerful. These almost protestant beliefs could not conquer, or in any way change, Michelangelo because too much of his work would have had to be denied. However, they must have to some extent disrupted his firm belief, as he had expressed it in his works, that by creating perfect physical beauty he had represented the essence of the supernatural and of the divine. It is true, however, that he felt the need for divine grace, and, from this point onwards, this had great bearing on his creative life. We find evidence of this in a drawing of the Piete made for Vittoria Colonna. When compared with the 1499 Piete we see clearly that the main objective is the thought of the Compassionate Christ and of the Redemption through Christ's Blood. The work turns openly towards the onlooker to admonish him, drawing his attention to the sacrifice of Golgotha. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: Study for the Colonna Piete Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : study |

| 62907 |

|

Study of a Head |

1530 Red chalk, 33,5 x 26,9 cm Casa Buonarroti, Florence Michelangelo seems to have conceived only one erotic painting involving a woman, the Leda and the Swan. The painting is lost, only this very fine read chalk study of a head has survived. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: Study of a Head Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : study |

| 52452 |

|

The Brazen Serpent |

1511 Fresco, 585 x 985 cm |

| 62902 |

|

The Brazen Serpent |

1511 Fresco, 585 x 985 cm Cappella Sistina, Vatican The scenes painted in the pendentives at the sides of prophet Jonah are characterized by the use of pronounced foreshortening. This is the case with the tangled group of Israelites who, in the scene of the Brazen Serpent, writhe in the throes of death, and, above all, with the crucified figure of Haman in the Punishment of Haman. In the Brazen Serpent, the mass of bodies poisoned by the snakes occupies the whole of the right part, spreading toward the center. The survivors are grouped on the left, eyes and arms turned imploringly toward the salvafic image of the brazen serpent. The cruel punishment of the Israelites for having spoken against God and Moses occupies a large part of the pendentive, with bodies intertwined in an indescribable tangle. This presented the artist with an opportunity for virtuosic foreshortening and twisting of the bodies, and also depicting contorted, screaming faces. Much admired by Vasari, the group is a striking forerunner of the spectacular motifs that were, in the following decades, typical of the current of Mannerism comprising Giulio Romano and Vasari himself. The Biblical story (Num. 21 :4-9) The Israelites, discontented with life in the desert, spoke out against God and Moses. They were punished with a plague of poisonous snakes which only increased their hardships. Many died of snakebite. When the people repented, Moses sought God's advice how they should be rid of the snakes. He was told to make an image of one and set it on a pole. Whoever was bitten would be cured when he looked upon the image. Moses accordingly made a serpent of brass on a tau-shaped (T) pole, which proved to have a miraculous curative effect. Representation in Art The Israelites are depicted writhing on the ground, their limbs entwined by snakes. Moses, sometimes with Aaron, stands beside the brazen serpent. John's gospel furnishes the typological parallel: 'This Son of Man must be lifted up as the serpent was lifted up by Moses in the wilderness.' Medieval art juxtaposed the subject with the serpent in the Garden of Eden entwining the Tree of Knowledge. Both probably derive from an ancient and widespread fertility image, the 'asherah', associated with the worship of Astarte, which consisted of a snake and a tree representing respectively the male and female elements. King Hezekiah destroyed the asherah, by inference the one made by Moses, at a time when the Israelites were relapsing into idolatry (II Kings 18:4). The presence and the identification of Moses in Michelangelo's fresco is debated. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Brazen Serpent Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : religious |

| 62903 |

|

The Brazen Serpent |

1511 Fresco Cappella Sistina, Vatican The cruel punishment of the Israelites for having spoken against God and Moses occupies a large part of the pendentive, with bodies intertwined in an indescribable tangle. This presented the artist with an opportunity for virtuosic foreshortening and twisting of the bodies, and also depicting contorted, screaming faces. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Brazen Serpent (detail) Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : religious |

| 52422 |

|

The ceiling |

1508-12 Fresco Cappella Sistina |

| 44879 |

|

The Ceiling of the Sistine Chapel |

mk176

1508-12

|

| 44257 |

|

The Conversion of Saul |

1542-45

Fresco,

625 x 661 cm |

| 62881 |

|

The Conversion of Saul |

1542-45 Fresco, width of detail 114 cm Cappella Paolina, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican The detail shows soldiers on the left side of the fresco. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Conversion of Saul (detail) Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : religious |

| 62882 |

|

The Conversion of Saul |

1542-45 Fresco, width of detail 101 cm Cappella Paolina, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican The detail shows St Paul and a soldier. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Conversion of Saul (detail) Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : religious |

| 31358 |

|

The Creation of Adam |

nn07

1508-1512 |

| 33478 |

|

The Creation of Adam |

mk86

c.1510

Fresco

c.280x570cm

Rome,Vatican,Sistine Chapel

|

| 39444 |

|

The crucifixion of the Hl. Petrus |

mk148

late fresco of Michelangelo(1475-1564) in the Cappella Paolina, Vatican |

| 62922 |

|

The Cumaean Sibyl |

1510 Fresco, 375 x 380 cm Cappella Sistina, Vatican The Cumaean Sibyl oppresses by the sheer weight of her bulk and a commanding ugliness. With the open folio bound in green and her two genii gazing at its pages over her shoulders she has become one of the Fates, a towering shape with human features. Whenever Sibyls are mentioned, the Cumaea at once comes to mind. In the art of Michelangelo and other painters her powerful presence overshadows every other Sibyl, even her younger and more beautiful sisters, such as the Delphica. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Cumaean Sibyl Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : religious |

| 44268 |

|

The Delphic Sibyl |

350 x 380 cm |

| 62916 |

|

The Delphic Sibyl |

1509 Fresco Cappella Sistina, Vatican In the center of the face - seen frontally, half in the light and half in a moderate shadow - there are traces of a crossincised to mark the vertical axis of the oval and the alignment of the eyes. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Delphic Sibyl (detail) Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : religious |

| 52436 |

|

The Deluge |

1508-09 Fresco, 280 x 570 cm |

| 23384 |

|

The Doni Tondo (nn03) |

c 1503/4 Tempera on panel diam 120 cm diam 47 1/4 in Galleria degli Uffizi Florence |

| 42964 |

|

The Entombment |

mk170

1497-1498

Oil on wood

161.7x149.9cm

|

| 44269 |

|

The Erythraean Sibyl |

360 x 380 cm |

| 62917 |

|

The Erythraean Sibyl |

1509 Fresco Cappella Sistina, Vatican Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Erythraean Sibyl (detail) Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : religious |

| 44261 |

|

The Fall and Expulsion from Garden of Eden |

1509-10

Fresco,

280 x 570 cm |

| 62908 |

|

The Fall of Phaeton |

1533 Chalk British Museum, London In Greek mythology Phaeton was the son of Helios, the sun-god. Helios drove his golden chariot, a 'quadriga' yoked to a team of four horses abreast, daily across the sky. Phaeton persuaded his unwilling father to allow him for one day to drive his chariot across the skies. Because he had no skill he was soon in trouble, and the climax came when he met the fearful Scorpion of the zodiac. He dropped the reins, the horses bolted and caused the earth itself to catch fire. In the nick of time Jupiter, father of the goods, put a stop to his escapade with a thunderbolt which wrecked the chariot and sent Phaeton hurtling down in flames into the River Eridanus (according to some, the Po). He was buried by nymphs. Phaetons's reckless attempt to drive his father's chariot made him the symbol of all who aspire to that which lies beyond their capabilities. The fall of Phaeton was a popular theme, common in Renaissance and Baroque painting, especially on ceilings in the later period. Phaeton, the chariot, and four horses, reins flying, all tumble headlong out of the sky. Above, Jupiter throws a thunderbolt. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: The Fall of Phaeton Date: 1501-1550 Italian , graphics : religious |

| 52432 |

|

The first bay of the ceiling |

1508-12 Fresco Cappella Sistina |

| 52439 |

|

The fourth bay of the ceiling |

1508-12 Fresco Cappella Sistina |

| 44255 |

|

The Holy Family with the infant St. John the Baptist |

c. 1506

Tempera on panel,

diameter 120 cm |

| 29033 |

|

The Holy Family with the Young St.John the Baptist |

mk65

Oil on panel

47 1/4in

Uffizi,Gllery

|

| 40292 |

|

The Holy Family with the Young St.John the Baptist |

mk153

c.1506

Oil on panel

|

| 40357 |

|

The Last judgment |

mk156

1536-40

Fresco

12.2x13.7cm

|

| 44896 |

|

The Last Judgment |

mk176

1536-41

|

| 56018 |

|

the last judgment |

mk247

1535 to 41 ,fresco,540x480 in,1370x1220 cm,sistine chapel,vatican city,ltaly |

| 52418 |

|

The Libyan Sibyl |

1511 Fresco, 395 x 380 cm |

| 42965 |

|

THe Madonna and Child with Saint John and Angels |

mk170

circa 1500

Tempera on wood

104.5x77cm

|

| 52444 |

|

The ninth bay of the ceiling |

1508-12 Fresco Cappella Sistina, |

| 52435 |

|

The second bay of the ceiling |

1508-12 Fresco Cappella Sistina |

| 52442 |

|

The seventh bay of the ceiling |

1508-12 Fresco Cappella Sistina |

| 56704 |

|

the sistine chapel ceiling |

mk247

1508 to 12,fresco ,sistine chapel,vatican city,ltaly |

| 52437 |

|

The third bay of the ceiling |

1508-12 Fresco Cappella Sistina |

| 39424 |

|

The victim Noachs |

mk148

around 1510, cover painting in the Sixtinischen chapel, Rome. after this victim God closed its pact with Noach gene 8.20) and it that" laws Noachs" given |

| 63011 |

|

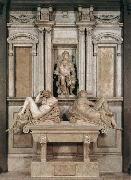

Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici |

1526-33 Marble, 630 x 420 cm Sagrestia Nuova, San Lorenzo, Florence Michelangelo received the commission for the Medici Chapel in 1520 from the Medici Pope Leo X (1513-23). The Pope wanted to combine the tombs of his younger brother Giuliano, Duke of Nemours, and his nephew Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino, with those of the "Magnifici", Lorenzo and his brother Giuliano, who had been murdered in 1478; their tombs were then in the Old Sacristy of San Lorenzo. The plans for the chapel which we still have, shows us that the Pope allowed Michelangelo a great freedom in his task. Not much of this vast plan was in fact carried out, yet it is enough to give us an idea of what Michelangelo's overall conception must have been. Each of the Dukes' tombs is divided into two areas, and the border is well marked by a projecting cornice. In the lower part are the sarcophagi with the mortal remains of the Dukes, on which lie Twilight and Dawn, Night and Day as the symbol of the vanity of things. Above this temporal area, the nobility of the figures of the Dukes and the subtlety of the richly decorated architecture which surrounds them represent a higher sphere: the abode of the free and redeemed spirit. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Painting Title: Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici , 1501-1550 |

| 63012 |

|

Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici |

1526-33 Marble Sagrestia Nuova, San Lorenzo, Florence Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Painting Title: Tomb of Giuliano de' Medici (detail) , 1501-1550 |

| 63013 |

|

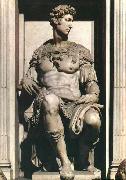

Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici |

1524-31 Marble Sagrestia Nuova, San Lorenzo, Florence Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Painting Title: Tomb of Lorenzo de' Medici (detail) , 1501-1550 Painting Style: Italian , sculpture Type: religious |

| 52426 |

|

Uzziah - Jotham - Ahaz |

1511-12 Fresco, 215 x 430 cm |

| 62909 |

|

View of the Chapel |

Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican Between 1537 and 1540, Antonio da Sangallo the Younger built the Pauline Chapel in the Vatican, as Pope's (Paul III) private chapel. In 1541 Michelangelo was asked to decorate the central parts of the two longer walls with two frescoes. The first, The Conversion of Saint Paul, was begun in 1542; the second, the Martyrdom of St Peter, was painted between 1546 and 1550. Before this, no one had ever attempted to place these two themes next to each other. Michelangelo portrays what is by this time his plan of life: death for the faith must follow conversion and be its confirmation. To Paul, who has fallen and has been forced to shut his eyes because of the brilliance of divine light, he gives his own face and makes Peter, nailed to the cross, in the supreme tension of the last moment of life, forcefully look at the spectator. Artist: MICHELANGELO Buonarroti Title: View of the Chapel Date: 1501-1550 Italian , painting : other |

| 44259 |

|

Zechariah |

1509

360 x 390 cm |

|

|

|

Prev 1 2

|

|

| Michelangelo Buonarroti

|

| b Caprese 1475 d Rome 1564

Born: March 6, 1475

Caprese, Italy

Died: February 18, 1564

Rome, Italy

Italian artist

Michelangelo was one of the greatest sculptors of the Italian Renaissance and one of its greatest painters and architects.

Early life

Michelangelo Buonarroti was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy, a village where his father, Lodovico Buonarroti, was briefly serving as a Florentine government agent. The family moved back to Florence before Michelangelo was one month old. Michelangelo's mother died when he was six. From his childhood Michelangelo was drawn to the arts, but his father considered this pursuit below the family's social status and tried to discourage him. However, Michelangelo prevailed and was apprenticed (worked to learn a trade) at the age of thirteen to Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449?C1494), the most fashionable painter in Florence at the time.

After a year Michelangelo's apprenticeship was broken off. The boy was given access to the collection of ancient Roman sculpture of the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo de' Medici (1449?C1492). He dined with the family and was looked after by the retired sculptor who was in charge of the collection. This arrangement was quite unusual at the time.

Early works

Michelangelo's earliest sculpture, the Battle of the Centaurs (mythological creatures that are part man and part horse), a stone work created when he was about seventeen, is regarded as remarkable for the simple, solid forms and squarish proportions of the figures, which add intensity to their violent interaction.

Soon after Lorenzo died in 1492, the Medici family fell from power and Michelangelo fled to Bologna. In 1494 he carved three saints for the church of San Domenico. They show dense forms, in contrast to the linear forms which were then dominant in sculpture.

Rome

After returning to Florence briefly, Michelangelo moved to Rome. There he carved a Bacchus for a banker's garden of ancient sculpture. This is Michelangelo's earliest surviving large-scale work, and his only sculpture meant to be viewed from all sides.

In 1498 the same banker commissioned Michelangelo to carve the Piet?? now in St. Peter's. The term piet?? refers to a type of image in which Mary supports the dead Christ across her knees. Larger than life size, the Piet?? contains elements which contrast and reinforce each other: vertical and horizontal, cloth and skin, alive and dead, female and male.

Florence

On Michelangelo's return to Florence in 1501 he was recognized as the most talented sculptor of central Italy. He was commissioned to carve the David for the Florence Cathedral.

Michelangelo's Battle of Cascina was commissioned in 1504; several sketches still exist. The central scene shows a group of muscular soldiers climbing from a river where they had been swimming to answer a military alarm. This fusion of life with colossal grandeur henceforth was the special quality of Michelangelo's art.

From this time on, Michelangelo's work consisted mainly of very large projects that he never finished. He was unable to turn down the vast commissions of his great clients which appealed to his preference for the grand scale.

Pope Julius II (1443?C1513) called Michelangelo to Rome in 1505 to design his tomb, which was to include about forty life-size statues. Michelangelo worked on the project off and on for the next forty years.

Sistine Chapel

In 1508 Pope Julius II commissioned Michelangelo to decorate the ceiling of the chief Vatican chapel, the Sistine. The traditional format of ceiling painting contained only single figures. Michelangelo introduced dramatic scenes and an original framing system, which was his earliest architectural design. The chief elements are twelve male and female prophets (the latter known as sibyls) and nine stories from Genesis.

Michelangelo stopped for some months halfway along. When he returned to the ceiling, his style underwent a shift toward a more forceful grandeur and a richer emotional tension than in any previous work. The images of the Separation of Light and Darkness, and Ezekiel illustrate this greater freedom and mobility.

After the ceiling was completed in 1512, Michelangelo returned to the tomb of Julius and carved a Moses and two Slaves. His models were the same physical types he used for the prophets and their attendants in the Sistine ceiling. Julius's death in 1513 halted the work on his tomb.

Pope Leo X, son of Lorenzo de' Medici, proposed a marble facade for the family parish church of San Lorenzo in Florence to be decorated with statues by Michelangelo. After four years of quarrying and designing the project was canceled.

Medici Chapel

In 1520 Michelangelo was commissioned to execute the Medici Chapel for two young Medici dukes. It contains two tombs, each with an image of the deceased and two allegorical (symbolic) figures: Day and Night on one tomb, and Morning and Evening on the other.

A library, the Biblioteca Laurenziana, was built at the same time on the opposite side of San Lorenzo to house Pope Leo X's books. The entrance hall and staircase are some of Michelangelo's most astonishing architecture, with recessed columns resting on scroll brackets set halfway up the wall and corners stretched open rather than sealed.

Poetry

Michelangelo wrote many poems in the 1530s and 1540s. Approximately three hundred survive. The earlier poems are on the theme of Neoplatonic love (belief that the soul comes from a single undivided source to which it can unite again) and are full of logical contradictions and intricate images. The later poems are Christian. Their mood is penitent (being sorrow and regretful); and they are written in a simple, direct style.

Last Judgment

In 1534 Michelangelo left Florence for the last time, settling in Rome. The next ten years were mainly given over to painting for Pope Paul III (1468?C1549).

|

|

All the Carl Larsson's Oil Paintings

All the Carl Larsson's Oil Paintings

Supported by oil paintings and picture frames

Copyright Reserved

|